In terms of music, many parallels have been drawn between expressionism and romanticism. Whilst very different in some ways, these two styles focus on portraying what the composer was feeling emotionally. They explored this in different ways though, romanticism using classical technique to invoke an emotion in the listener; and expressionism throwing most rules out the window if they didn’t suit the piece in question. For this reason, expressionist music often ended up being dissonant and fragmented. This lead to a very intense musical experience for both the composer, the performers, and the listeners. (ThinkQuest, “Expressionism”)

The forerunner of the expressionist movement was undoubtedly Arnold Shoenberg. With his twelve tone system he revolutionised how music was written. The twelve tone system was a method of composition in which each of the twelve notes in the chromatic scale are played as often as one another. This prevents emphasis being placed on one note and therefore the piece does not have a set key. (Perle, 1977) Schoenberg’s twelve tone system expanded the horizons of every expressionist composer, further opening their options to express their emotions through dissonance and atonality.

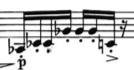

An excellent example of expressionist composition is Arnold Schoenberg’s Gavotte in Op. 25. This was the first piece to be composed entirely in tone rows, and therefore entirely without a key. The piece is made up of six movements which are composed using a single row. For this piece to be analysed properly it has to be looked at in terms of patterning and shape, as there is no ‘home key’ and therefore no real harmony. The first motif in the piece is established in bar 1: starting on a Db, moving to Gb, Eb, then Ab.

This motif is repeated throughout the first movement of the piece in different tones such as Bb to A to G to Db in bar 3 and Ab to Cb to Gb to C in bar four.

Although not exactly alike, when heard in context they sound very similar. This motif repetition makes this piece much easier to listen to and to understand. There is also an awful lot of call and response in this piece. As outlined in the musical quote taken of bar 2, the bass line begins with G, A, F; the treble then responds with the first motif of the piece. This pattern continues for the next two repetitions of the motif. Call and response is heavily used in expressionist pieces to help the listener find some sense of logic in pieces that would otherwise be too disconnected for the untrained ear to understand.

Another motif pattern is created in bar 11, continuing the call and response but elaborating so that instead of one hand playing at a time they are now overlapping. Similar to the previous motif, Schoenberg keeps this one simple: only a chord slurring to a single staccato quaver. This adds a real finality to the note and creates a jarring feeling in the piece. Underneath this motif, continuous staccato quavers are being played. Even though they are continuous, the jarring feeling is still sustained because of the staccato nature of the notes.

This piece of music is an excellent example of the parallels we can draw between expressionist art and music. Exaggerated characteristics including colour in art, and articulation and dynamics in music; distorted shapes in art and dissonant sounds in music; and the blunt way that both of these art forms portray difficult emotions that the artists were feeling tie expressionist art and music together very tightly in the viewers and listeners mind.

Bibliography:

“German Expressionism.” MoMA. Museum of Modern Art, n.d. Web. 22 Mar. 2014. <http://www.moma.org/explore/collection/ge/artists>.

Munch, Edvard, and J. Gill Holland. The Private Journals of Edvard Munch: We Are Flames Which Pour Out of the Earth. Madison, Wis.: University of Wisconsin Press, 2005. Print.

Perle, George. Serial composition and atonality: an introduction to the music of Schoenberg, Berg, and Webern. 4th ed. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1977. Print.

Puddock, David . “What is Expressionist Art?.” Garp’s World. N.p., n.d. Web. 22 Mar. 2014. <http://www.garpsworld.com/art/expressionist/expressionist_art.htm>.

Shabi, K. “Meaning of The Scream.” Legomenon. N.p., 12 July 2013. Web. 19 Mar. 2014. <http://legomenon.com/meaning-of-the-scream-1893-painting-by-edvard-munch.html>.

ThinkQuest. “Expressionism.” ThinkQuest.org. N.p., n.d. Web. 24 Mar. 2014. <http://library.thinkquest.org/27110/noframes/periods/expressionism.html>.

Wolf, Justin. “Expressionism Movement, Artists and Major Works.” TheArtStory.org. N.p., n.d. Web. 22 Mar. 2014. <http://www.theartstory.org/movement-expressionism.htm>.

March 31st, 2014 at 9:40 am

Hey Sian – this looks fantastic so far! Good analysis, particularly with motiff/call & response – further discussion could be had regarding how this pattern is moved – i.e does it ascend chromatically in any way each time, or is it completely randomized? Also, how are ‘chords’ used in this piece – chords in this case is not the chords we typically here in traditional harmony, but rather, what effect do chords have and is there a pattern to their construction? (these relationships will most likely be intervallic – look for similiar intervals across groupings, i.e a perf 4 with a min 3rd on top etc…)